Beyond the Lecture Hall: How Adaptive Scaffolding Empowers Mature Learners in Higher Education

Article Date | 23 September, 2025

By Yunus Ali, PAT co-ordinator, LSST Elephant and Castle, and Dr Rashi Bansal, Course Co-ordinator Health, L3&4, LSST Elephant and Castle.

Mature learners, defined as students aged 21 and above, are a vital and growing part of UK higher education. They often juggle study alongside work, caregiving, and other responsibilities, bringing with them rich life experience, intrinsic motivation, and resilience. At the same time, they may encounter challenges such as re-engaging with academic literacies, balancing external commitments, or rebuilding confidence in their academic abilities (Merrill, 2007).

To address these needs, adaptive scaffolding offers a powerful approach. Put simply, adaptive scaffolding refers to tailored, responsive support that gradually reduces as learners build skills and independence. It enables educators to meet mature learners where they are, providing the right level of structure at the right time.

This practice brief translates theory into action, offering educators practical strategies, timelines, and success metrics to foster independence, confidence, and long-term academic success, empowering mature learners beyond the lecture hall.

Andragogy and Scaffolding: Aligning Adult Learning with Supportive Instruction

Scaffolding is particularly effective for mature learners because it aligns with Andragogy, Malcolm Knowles’ (1980) adult learning theory. Key principles include:

- Self-Concept: Adults are self-directed; scaffolding gradually shifts responsibility from instructor to learner.

- Experience: Life and work experience inform learning; scaffolding connects new knowledge to prior experience (Merriam & Bierema, 2014).

- Readiness to Learn: Adults engage when learning solves real problems; scaffolding frames tasks around authentic challenges (Rosenshine and Meister, 1992).

- Orientation to Learning: Adults are problem-centred rather than subject-centred; scaffolding breaks down complex tasks into manageable steps.

- Motivation: Adults are intrinsically motivated; scaffolding builds confidence and reinforces self-directed engagement (Bandura, 1977).

Operational Definition of Scaffolding: A temporary, structured support system that helps learners achieve tasks they could not complete independently, with support gradually withdrawn as proficiency develops (Vygotsky, 1978; Bruner, Wood et al., 1976).

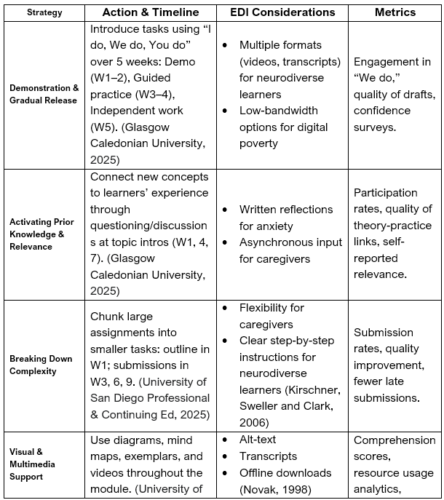

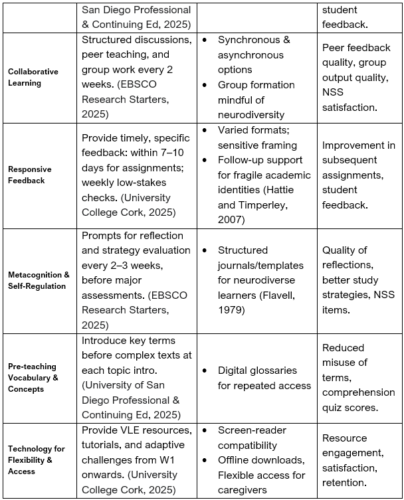

Actionable Scaffolding Strategies for Mature Learners

The following plan outlines practical strategies for integrating adaptive scaffolding into teaching. Each approach is designed with a gradual release timeline, attention to equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI), workload guidance for educators, and measurable outcomes to track effectiveness. Together, these elements provide a structured yet flexible framework that supports both learners and staff.

Implementing Adaptive Scaffolding into Practice

Adaptive scaffolding is not just a teaching strategy; it’s a mindset. At its core, it recognises that mature learners bring unique experiences, strengths, and challenges into the classroom. When used thoughtfully, scaffolding supports autonomy while still offering the right level of guidance at the right time. It helps bridge gaps in knowledge, encourages confidence, and nurtures the ability to think critically and learn independently (Puntambekar and Hubscher, 2005).

What makes adaptive scaffolding particularly powerful in higher education is the way it aligns with andragogical principles, the idea that adults learn best when teaching acknowledges their prior knowledge, is problem-centred, and has clear relevance to their personal and professional goals. Adding an equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) lens makes this even stronger, ensuring that the learning environment values diverse perspectives and reduces barriers that some students may face.

When these elements come together, educators don’t just help students succeed in a single module or degree. They equip them with the skills, mindset, and confidence to continue learning long after formal education ends, embodying the very essence of lifelong learning.

Nurturing Independence Through Adaptive Scaffolding

Adaptive scaffolding goes beyond being a classroom technique; it is a philosophy of teaching and learning. At its heart, it acknowledges that mature learners are not empty vessels waiting to be filled but individuals with prior knowledge, experiences, and ambitions. When implemented thoughtfully, scaffolding balances guidance with freedom. It respects learner autonomy while still offering timely support to bridge knowledge gaps. Over time, this approach helps learners build confidence, sharpen their critical thinking, and strengthen their ability to direct their own learning.

What makes adaptive scaffolding so powerful in higher education is how naturally it complements andragogy, the principles of adult learning. Adults are motivated when they see the relevance of what they are learning, when they can draw on their existing experience, and when the learning process feels collaborative rather than prescriptive. By layering this with an EDI perspective, educators also ensure that diverse backgrounds, learning styles, and barriers are recognised and addressed, making higher education more inclusive and equitable.

Ultimately, the aim is not just academic success within a module or programme. It is about equipping mature learners with the mindset and skills to continue growing well beyond the lecture hall: in their careers, communities, and personal lives. Adaptive scaffolding, when embraced as a philosophy, helps cultivate exactly that: confident, self-directed, and lifelong learners.

References

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

EBSCO Research Starters (2025) Scaffolding and adult learning: an overview.

Flavell, J.H. (1979) ‘Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry’, American Psychologist, 34(10), pp. 906–911.

Glasgow Caledonian University (2025) Adaptive scaffolding for mature learners: teaching guide.

Hattie, J. and Timperley, H. (2007) ‘The Power of Feedback’, Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81–112.

Kirschner, P.A., Sweller, J. and Clark, R.E. (2006) ‘Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching’, Educational Psychologist, 41(2), pp. 75–86.

Knowles, M.S. (1980) The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. 2nd ed. Chicago: Follett Pub. Co.

Merriam, S.B. and Bierema, L.L. (2014) Adult Learning: Linking Theory and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Merrill, M.D. (2007) ‘A Task-Centered Approach to Instructional Design’, Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 18(1), pp. 17-32.

Novak, J.D. (1998) Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Puntambekar, S. and Hubscher, R. (2005) ‘Tools for Scaffolding Students in a Complex Learning Environment: What Have We Learned?’, Journal of Learning Sciences, 14(1), pp. 1-36.

Rosenshine, B. and Meister, C. (1992) ‘The Use of Scaffolds for Teaching Higher-Level Cognitive Strategies’, Educational Leadership, 49(7), pp. 26-33.

University College Cork (2025) Supporting mature learners through adaptive scaffolding

University of San Diego Professional and Continuing Education (2025) Scaffolding strategies for higher education.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J.S. and Ross, G. (1976) ‘The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), pp. 89-100.