Teaching Health and Social Care: an exemplar of excellence

Article Date | 13 August, 2021

By Dr Wendy Wigley, Head of Student Life-cycle

Health and Social Care relates to services that are available from health and social care providers. Much of these services, albeit wide ranging, focus on the ability to improve physical, emotional and social support to help people live their lives. Therefore, to quote Gestault Theory excellence in teaching health and social care requires us to recognise that we are ‘more than the sum of our parts’. Teaching and learning are a holistic endeavour for all those involved.

Through my long and enjoyable career in teaching and supporting learners studying for careers in health and social care, one thing I have learnt is that people enter health and social care professions because they have an affiliation with their fellow human beings. In turn, a recognition that caring for another is a great gift for both the care provider and the recipient.

Another thing I have learnt is that no one enters the health and social care profession to get ‘rich’, even those who run care and nursing homes are acutely aware of the rigors of regulation, intended to safeguard clients, staff and to provide quality care.

At LSST, teaching is not simply a matter of standing in front of a class or, with remote learning, sitting in front of a computer screen and reciting what you know. An LSST learning experience is a special form of synergy and communication in which our personality, voice, movement, expressions and eye-to-eye contact can either help or hinder the learning process. But when it comes to health and social care, the very topic, delivery, and manner of speaking with a commitment to peoples’ lives positively influences student learning, attentiveness and interaction. Yet, how can one teach health and social care when so much of it is complex and interrelated. Here are my findings:

Calling

Calling is defined as ‘a strong urge towards a particular way of life or career; a vocation.’ (OED online). Calling or vocation has been traditionally associated with the Health and Social profession (Lundmark, 2007). Florence Nightingale referred to ‘calling’ as this ‘precious gift’ and viewed this as the essential constituent of a good and worthy nurse.

Likewise, Mary Seacole, ‘had from early youth a yearning for medical knowledge and practice…’ Consequently, health and social care professionals and those that teach in this sector, have an ideology based upon philanthropic aspiration, for themselves and the care they provide. This aspiration is often based upon individual experience, or the influence of significant role models.

Role Models

The power of role modelling in teaching Health and Social Care should not be underestimated. Learners coming into health and social care professions often come from diverse backgrounds and are of varying ages. Drury et al’s (2008) grounded theory study considered the impact of health and social care education on mature learners and found negative feelings of isolation, alienation, fear of failure and minimal confidence in academic abilities are often balanced with positive themes such as high levels of motivation and personal reasons for undertaking the course. It is important to recognise that the learning for each student will be different, depending on their past experiences of life, the sector, and their altruistic desire. Positive role models can gently nurture and help personal growth and learning, at the individual’s own pace.

The curricula

The contexts and contents of any curriculum in health and social care is based on students requiring and merging knowledge and skills related to the:

Within health and social care these five elements, while often taught separately as individual units or modules of learning, do not sit discretely, they are intended at the end of the learning period, to be brought together to support and enable the student to become effective in decision making and providing quality care.

This is the ongoing challenge for those teaching in health and social care, and indeed of the learners who try to grapple in applying the content of these elements to the context in which they intend to, or are practising. Reflection is essential in enabling learning in health and social care to take place and a good reflection helps the consolidation of all five elements into the learning that is needed to become a safe and effective professional in health and social care.

Reflection

Reflection is not an easy skill to teach, for some reflection comes reasonably naturally, they are ‘reflective learners’ (Honey and Mumford, 1992), however, learning is a skill that needs to be practised. Even natural reflectors need to improve their skills (of interest see Dr Peter Honey’s 2014 lecture).

Reflection in health and social care enables understanding of ‘self’ in context and the application of theory to professional practise. As such reflection is a good way for learners in health and social care to explore the individual and unique experience of their learning. Like all learning a framework for reflection can help learners process an experience and find for themselves the learning that took place.

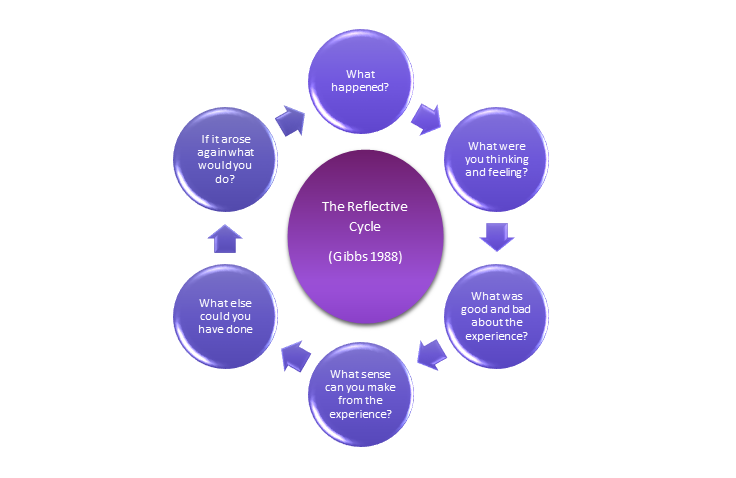

Gibbs reflective cycle (1988) is often used to enable learners in health and social care explore experiences. Gibbs developed a six-phase framework as shown below:

Gibbs reflective cycle is a useful starting point for learners new to reflection and reflective practice, however it does not necessarily allow for the learner to fully consider the knowledge and skills they might have, or have not drawn upon to make sense of an experience.

Carper’s (1978) seminal work on reflection explored ‘Fundamental Ways of Knowing’, this framework was further expanded by White (1995) who included added ‘Social Political knowing’. The reflective model depicted below gives a framework by which learners in health and social care can combine the five elements that are embedded in the curriculum, and effectively apply these to the learning from a given situation. A description of these ways of knowing and their application to the five elements of a health and social care curriculum are shown below:

…and breathe…

Quite often when we teach there is a desire to have all the answers. We believe that we are seen as the ‘expert’ in what we teach. This is not so, as we have seen in the model above, knowledge is always co-created, by interaction with others (including our students), physical resources and ourselves (by reflecting on what we do). Knowledge acquisition takes time – which is why a full-time degree is a minimum of 3 years. In teaching (and learning) there is no need rush and try to force the learning (or teaching) to happen. Life is complex and busy and so are teaching and learning, both can take their toll on health and wellbeing.

Lamm (2021) has written a helpful blog about the need to ‘pause’ in our lives, regardless of the activity we are undertaking. Learners need to be able to pause in their learning and likewise teachers should pause in their teaching. Pausing temporarily rests the mind and reflective activities enable us to look at an experience through a different lens. Dewey (2007) saw children as role models for ‘excellence’ because ‘Children proverbially live in the present; that is not only a fact not to be evaded, but it is an excellence’. A simple model reflection designed by LSST students is PACT pausing, being attentive, calming our mind and being thankful for the here and now in our lives… be that as teacher…or learner.

References

I am trying to locate some good reading in regard to Teaching Health and Social Care in a Secondary School. Do you have any recommendations?